Here’s a synthesis of 6BrNapAV that I completed and wrote up a while ago. It comprises of 6 steps, each step is followed by some comments which highlight issues that may arise.

tert‐Butyl 2‐[(6‐bromonaphthalen‐2‐yl)oxy]acetate (EC-004)

To a solution of 6-bromo-2-naphthol (11.5 g, 51.6 mmol) in acetone (130 mL) was added potassium carbonate (1 eq, 7.13 g) and the mixture was stirred overnight in a flask equipped with reflux condenser and CaCl2 drying tube. After this time, tert-butyl chloroacetate (1.05 eq, 7.38 mL) and another portion of potassium carbonate (1 eq, 7.13 g) were added and the mixture was heated at reflux (70 °C oil bath temperature) overnight. After this time, TLC (5:95 ethyl acetate/n-hexane) appeared to indicate the absence of starting naphthol. The reaction mixture was evaporated to dryness under reduced pressure and the residue was partitioned between dichloromethane and water and stirred until all solids had dissolved. The layers were separated and the aqueous phase was extracted with dichloromethane. The combined organics were washed in turn with water, and brine, dried (MgSO4), filtered and evaporated under reduced pressure, affording a dark brown oil (17.0 g). Proton NMR of this indicated the presence of a small amount of starting naphthol. Column chromatography (eluting with 4:6 dichloromethane/n-hexane, wet-loaded, 5×8 cm) afforded the title compound as a yellow oil which solidified on standing (14.5 g, 83 %). This was used in the next step without further purification. A small amount of an unidentified impurity is seen in the proton NMR around 4.25 ppm.

δH (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) 8.12 (1H, d, J 1.88, HAr), 7.85 (1H, d, J 9.00, HAr), 7.76 (1H, d, J 8.84, HAr), 7.57 (1H, dd, J 8.74, 2.06, HAr), 7.29 (1H, d, J 2.48, HAr), 7.25 (1H, dd, J 8.90, 2.58, HAr), 4.77 (2H, s, CH2), 1.43 (9H, s, C(CH3)3). δC (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) 167.51 (C=O), 155.90, 132.60, 129.84, 129.32, 129.30, 128.89, 128.66, 119.47, 116.52, and 107.30 (CAr), 81.44 (C(CH3)3), 65.07 (CH2), 27.65 (C(CH3)3). HRMS (EI) m/z: [M]+ calcd for C16H1779BrO3 336.0361; found 336.0371, [M]+ calcd for C16H1781BrO3 338.0342; found 338.0320.

Comments on 6-Br-2-NapOt-Bu synthesis

The 6-Br-2-NapOH building block is not commercially available so we have to make it ourselves starting from 6-bromo-2-naphthol. This synthesis of 6-Br-2-NapOt-Bu is analogous to that of all other Nap-tert-butyl esters. We used to make our own 2-NapOH (before we realised that you can buy it) in exactly the same way.

I’ve never really figured out the official reason for the excess of base (potassium carbonate, 2 equivalents): looking at the reaction scheme, only one equivalent should be required. It may have to do with pre-drying the solvent (anhydrous potassium carbonate is a mild dessicant) and which is why the solution of the naphthol is stirred with potassium carbonate for a while before the chloroacetate is added. Some published similar syntheses use excess potassium carbonate and pre-stir it in the solvent, others don’t. Of course they all claim good yields. In any case, excess potassium carbonate won’t hurt the reaction and is easily removed later.

The reaction can be sluggish and reflux is required. tert-Butyl bromoacetate may be used instead of the chloroacetate and I have in the past added catalytic potassium iodide to try to speed up the reaction/push it to completion: I can’t say I noticed much improvement in reaction speed or yield.

It can be tempting to use a large excess of the chloroacetate to drive the reaction to completion. Surprisingly, this does not seem to help a lot and the unreacted tert-butyl chloroacetate is surprisingly difficult to remove from the product. If you need a clean sample of the product at this step (e.g. for data), it is best not to use a large excess of chloroacetate. The “unidentified” impurity at 4.25 ppm in the proton spectrum above is likely a small amount of tert-butyl chloroacetate, even though the material was purified by column chromatography and only 1.05 equivalents were used to begin with. If, on the other hand, a clean compound is not required at this stage, any remaining chloroacetate and naphthol should wash out in the next step so no column is necessary.

2‐[(6‐Bromonaphthalen‐2‐yl)oxy]acetic acid (EM-002)

To a solution of EC-004 (18.5 g, 54.9 mmol) in chloroform (80 mL) was added trifluoroacetic acid (ca. 10 eq, 42 mL) and the mixture was stirred overnight. After this time, it was poured into diethyl ether (500 mL), stirred for 1 hour, then filtered. The solid in the filter was washed with several portions of diethyl ether and dried under vacuum. The title compound was thus obtained as a white solid (12.5 g, 81%).

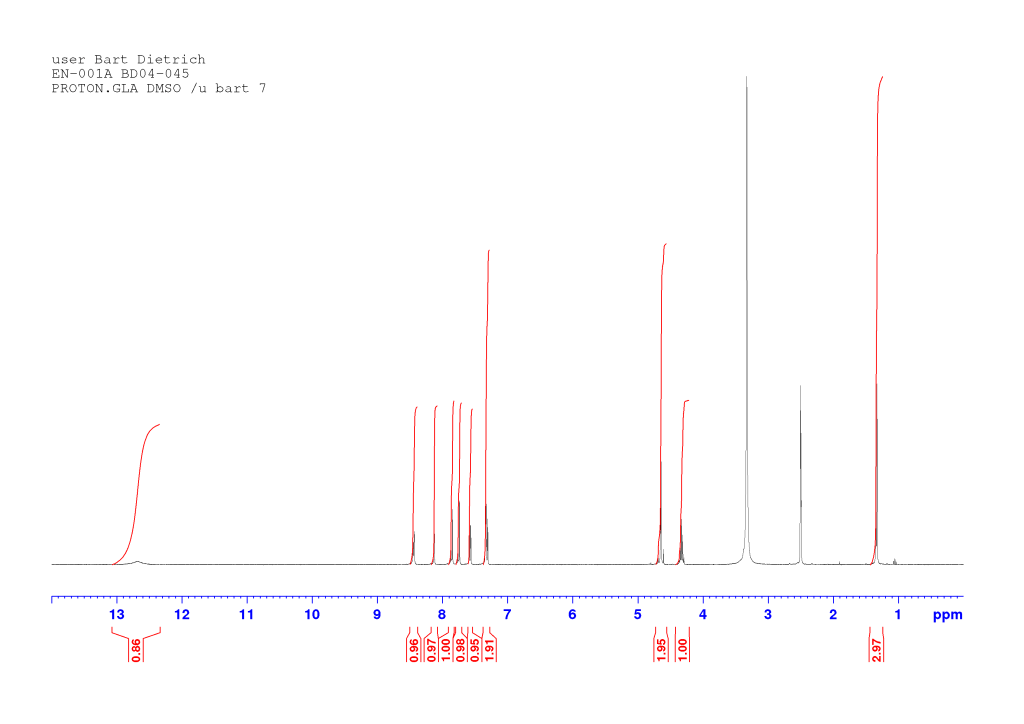

δH (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) 13.11 (1H, br s, COOH), 8.12 (1H, d, J 1.92, HAr), 7.85 (1H, d, J 9.00, HAr), 7.77 (1H, d, J 8.80, HAr), 7.57 (1H, dd, J 8.76, 2.04, HAr), 7.32 (1H, d, J 2.48, HAr), 7.26 (1H, dd, J 8.96, 2.60, HAr), 4.80 (2H, s, OCH2). δC (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) 169.96 (C=O), 156.06, 132.69, 129.87, 129.38, 129.33, 128.97, 128.72, 119.64, 116.54, and 107.16 (CAr), 64.58 (OCH2). HRMS (ESI) m/z: [M+Na]+ calcd for C12H979BrNaO3 302.9627; found 302.9629.

Comments on 6-Br-2-NapOH synthesis

The deprotection of the tert-butyl ester EC-004 is analogous to most other such deprotections that we do. In general, the tert-butyl ester is dissolved in chloroform (or dichloromethane) and a large excess (here, 10 equivalents) of trifluoroacetic acid is added. The reaction is stirred until complete. This can be monitored by TLC but most often we just let it stir overnight and assume it’s gone to completion. Another method to check for reaction completion is by pipetting a couple of drops of the reaction mixture into a vial containing a couple of mL of diethyl ether: if no precipitate forms, or the precipitate looks gummy or sticky, then the reaction is not complete. If a fine powdery precipitate forms then the reaction may be complete, or is close to getting there at the very least. The reaction product is often soluble in the chloroform/TFA reaction solvent but sometimes it starts precipitating out as the reaction progresses. When the reaction is complete (or assumed complete), it is poured into diethyl ether. The product is much less soluble in diethyl ether than chloroform/TFA and so it precipitates out of the mixture and can be filtered off.

The product obtained here still contains a small amount of unreacted starting material (see annotated spectrum below). This amount is about 1.6%. How to calculate this is explained here. The starting material does not interfere with the next step in the synthesis and so was left as is in this writeup but if you need a clean sample (e.g. for data), there are two ways of going about this. You can try recrystallisation, although for NapOH compounds it can be difficult to find a suitable solvent as these compounds are fairly soluble in many solvents. Or you can just put it back into more TFA/chloroform and stir for longer. Because the material is a carboxylic acid, silica column chromatography is not a good option.

The proton spectrum also shows a small peak at 8.3 ppm: this is a small amount of residual chloroform. If you’re accustomed to deuterated chloroform for your NMR samples, this will take some getting used to: we generally used deuterated DMSO and chemical shifts for common solvents and impurities are all different in DMSO-d6 from what they are in CDCl3. See “NMR solvent peaks” under useful links. Also note the water peak. In DMSO-d6, this is usually fairly sharp and at 3.3 ppm. Here it is broad and around 3.5 ppm. Broadening and shifting of the water peak to the left of the spectrum indicates the presence of a small amount of residual acid (TFA). The further away from 3.3 ppm the water peak is, the more acid is present. Here it’s a fairly small amount but still noticeable. A small amount of residual acid will not interfere in the next step and so it was left as is (see paragraph about washing out the TFA below).

Deprotection of tert-butyl esters (and Boc groups) is simple on paper (dissolve in chloroform, lob in the TFA and stir) but it has its quirks. There are four main things to note (and they apply equally to the deprotection of Boc groups):

- Although the reaction is formally catalytic in nature, you will be waiting forever if you only use a catalytic amount of TFA. For a reasonably fast reaction, you need an excess of TFA (at least a few equivalents, 10 equivalents are used in this writeup).

- The total concentration of TFA in the reaction mixture is also important: it needs to be high or you’ll be waiting forever for the reaction to complete. I usually go for 1 part of TFA in 2 parts chloroform (approx. 33%, in this writeup this was 80 mL chloroform and 42 mL TFA) but using 1:1 (50%) will not hurt either. The general procedure to figure out how much TFA and chloroform you’ll need is as follows:

- Calculate the amount of TFA for 1 equivalent. For example, let’s say you have 5 g of tert-butyl ester and one equivalent of TFA turns out to be 0.5 mL.

- Multiply the amount of TFA by the number of equivalents you intend to use. For example, let’s say you intend to use (at least) 4 equivalents, that makes 4×0.5=2 mL TFA.

- Taking the target concentration, calculate the amount of chloroform you will need. If you’re going for one part TFA in two parts chloroform, you will need 2×2=4 mL chloroform for your 2 mL TFA.

- Check if your starting material will actually dissolve in the volume of chloroform chosen. If not, scale up both the chloroform and TFA to a reasonable volume. This keeps the concentration of TFA in chloroform constant but of course increases the number of equivalents used: that’s ok, you were planning to use at least that number of equivalents. In the current example, 5 g of starting material is unlikely to dissolve in just 4 mL of chloroform. So scale it up by e.g. 10 times: this means 10×4=40 mL chloroform and 10×2=20 mL TFA. Which means you’ll be using 10×4=40 equivalents of TFA rather than the originally planned 4 equivalents.

- The product is precipitated out by diethyl ether. The volume of ether needs to be substantial. I usually go for at least 2-3 times the reaction volume. If the reaction volume is large to begin with, it can be reduced by concentrating the reaction on a rotavap (removing most of the chloroform and some of the TFA) before mixing with diethyl ether.

- The order of mixing of the reaction mixture and diethyl ether matters! Most often people will just add the diethyl ether to the reaction mixture. This can lead to the formation of gummy lumps of product which stick to the stirrer bar and flask walls. What’s worse, these lumps can lock in TFA/chloroform which then does not get diluted as more ether is added. Better results are obtained if the reaction mixture is added in small portions (or even dropwise from a dropping funnel) to a large amount of quickly stirred diethyl ether. The product then usually precipitates out as a fine solid which doesn’t stick to everything (unless the reaction is not complete, in which case the precipitated solid will be sticky since it’s coated with sticky/oily starting material).

Finally, washing out excess TFA/chloroform from the product deserves a mention. Often, people will just wash the product in the filter with several portions of diethyl ether. The question is, how do you know when you’ve washed out all of the TFA/chloroform? What if you have aggregated lumps of product in the filter that have locked in some TFA/chloroform and that the ether will simply bypass rather than penetrating and washing out the TFA/chloroform from the inside? This is why the above proton NMR shows traces of chloroform and TFA! I’ve found the best approach is to wash the solid in the filter with a couple of portions of diethyl ether, then transfer the solid into a conical flask, add a generous amount of ether, stir vigorously (with the stirrer bar big enough and moving fast enough to break up any lumps) for 30 minutes, and then filter again. Then repeat this once more. This usually removes all of the TFA and chloroform.

Methyl (2S)‐2‐{2‐[(6‐bromonaphthalen‐2‐yl)oxy]acetamido}propanoate (EM-003)

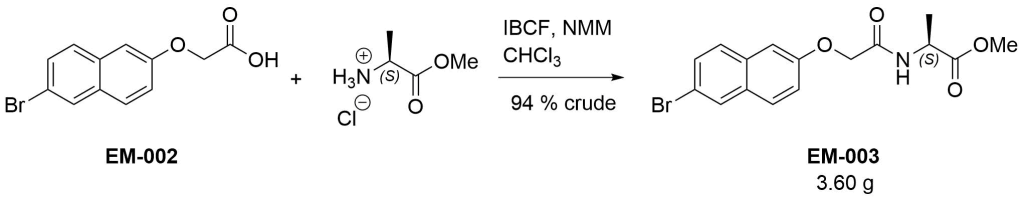

To a solution of EM-002 (2.96 g, 10.5 mmol) in chloroform (70 mL) was added isobutyl chloroformate (1.01 eq, 1.38 mL) followed by N-methylmorpholine (1.1 eq, 1.27 mL). After 10 minutes, L-alanine methyl ester hydrochloride (1 eq, 1.47 g) and another portion of N-methylmorpholine (1.1 eq, 1.27 mL) were added and the reaction was stirred overnight. It was then diluted with chloroform, washed with 1M hydrochloric acid and brine, dried (MgSO4), and evaporated under reduced pressure. The resulting cream solid (3.60 g, 94 % crude) was used as is for the next step. A small amount was purified via column chromatography (1:9 ethyl acetate/dichloromethane) to afford an analytical sample.

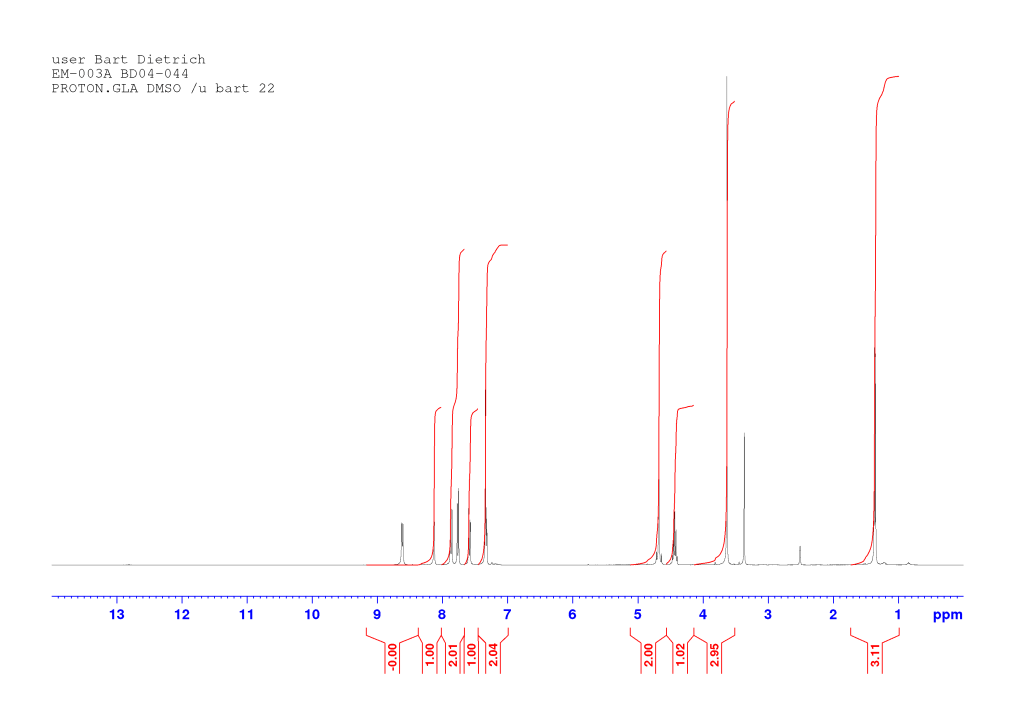

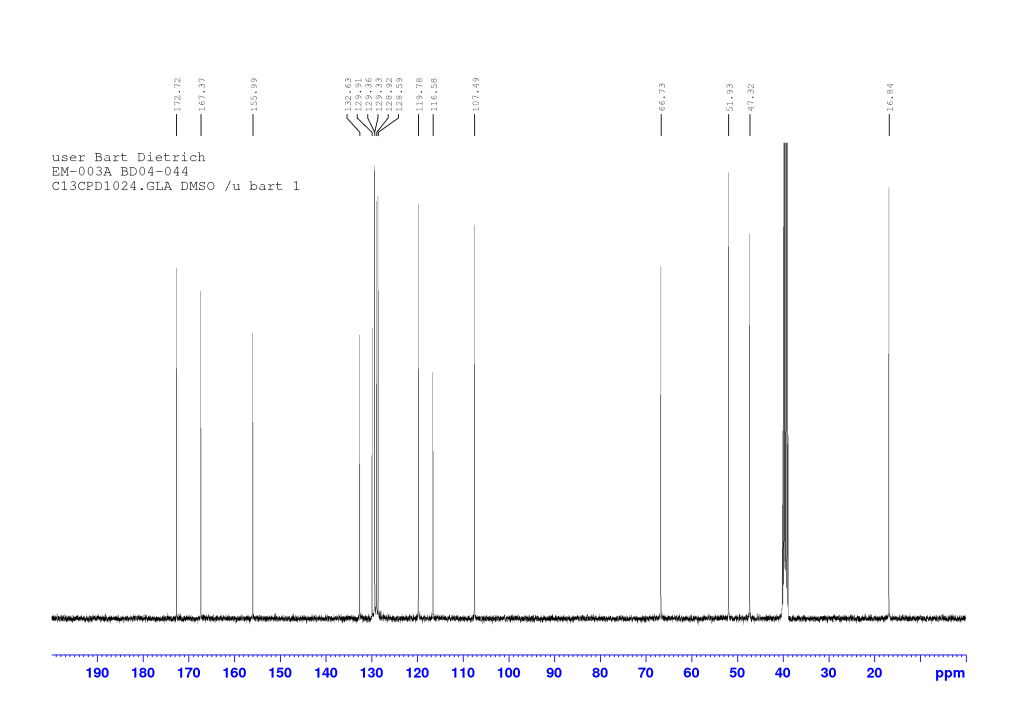

dH (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) 8.60 (1H, d, J 7.36, NH), 8.13 (1H, d, J 1.92, HAr), 7.88-7.85 (1H, m, HAr), 7.76 (1H, d, J 8.84, HAr), 7.58 (1H, dd, J 8.74, 2.06, HAr), 7.33-7.30 (2H, m, HAr), 4.68 (1H, d, J 14.73, OCHaHb), 4.63 (1H, d, J 14.73, OCHaHb), 4.44-4.37 (1H, qd, J 7.31, 7.28, CH*), 3.62 (3H, s, OCH3), 1.34 (3H, d, J 7.28, CH*CH3). dC (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) 172.72 and 167.37 (C=O), 155.99, 132.63, 129.91, 129.36, 129.33, 128.92, 128.59, 119.78, 116.58, and 107.49 (CAr), 66.73 (OCH2), 51.92 (OCH3), 47.32 (CH*), 16.84 (CH*CH3). HRMS (ESI) m/z: [M+Na]+ calcd for C16H1679BrNNaO4 388.0155; found 388.0154.

Comments on 6-Br-2-NapAOMe synthesis

This synthesis is pretty typical of all IBCF/NMM-mediated couplings in our lab. The reasons for using the IBCF/NMM reagent combination rather than one of the myriad available peptide coupling agents are lost in the mists of time but probably have to do with ease of workup, low cost of reagents, and because the method works well enough.

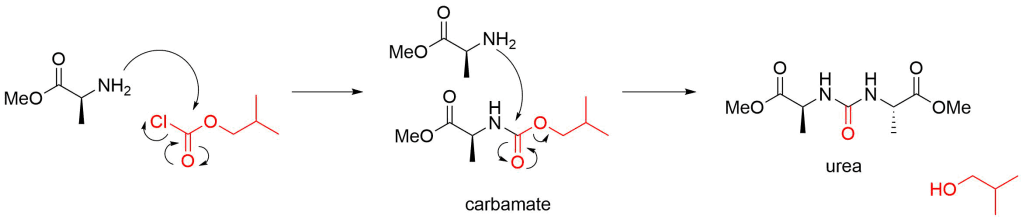

The order of addition of reagents is important in this reaction. The IBCF activates the carboxylic acid by forming a mixed anhydride. It is this mixed anhydride which subsequently reacts with the amine to give the product. It follows that the IBCF must be combined with the acid (EM-002 in this example) and NMM before the amine (alanine methyl ester hydrochloride in this example) is added. One equivalent of base (NMM) is required to mop up the HCl formed.

If the amine is combined with IBCF first, it will react to give a carbamate or urea. Not what you want and there’s no going back from this: your reaction will need to go in the bin.

The mixed anhydride then reacts with the amine to give your final compound. Another equivalent of base (NMM) is required to free up the amine from the hydrochloride. Note how the liberation of CO2 is the driving force and ensures that there’s no going back. The formation of carbon dioxide also means that you shouldn’t stopper your reaction tightly, particularly on large scales!

Two equivalents of base are required (in total). Whether these are added together at the beginning or separately in two portions at each step doesn’t really matter. An excess of base is not detrimental either. Sometimes a little more NMM at the very start helps to dissolve the acid before the IBCF is even added.

This reaction is sometimes performed under ice/water cooling rather than at room temperature. I have not really seen much difference in terms of yield between the two approaches. A pink-coloured (and unidentified) impurity is occasionally formed after addition of IBCF. Running the reaction under ice/water cooling may help reduce the amount of this impurity. In any case, it washes out in the next step.

The reaction of the acid with IBCF to form the mixed anhydride is pretty quick and no major waiting time is required before adding the amine (10 minutes are allowed in the current example). Waiting too long may encourage the formation of more of the pink impurity. Generally it is sufficient if you add the IBCF (and NMM) and then go weigh out the amine. By the time you’ve come back from the balance enough time should have elapsed.

The reaction workup involves washing with 1M hydrochloric acid (to remove excess NMM), water, then brine. The HCl washing step removes any excess base (not just NMM) so it is beneficial to use a slight excess of the amine (here, alanine methyl ester hydrochloride) to drive the reaction to completion. The excess alanine methyl ester will be washed out at the HCl washing step. If you used a slight excess of the acid component instead (here, EM-002), it won’t wash out and will be present in your product. A slight excess can be, for instance, 1.05 equivalents of alanine methyl ester hydrochloride to 1 equivalent of EM-002.

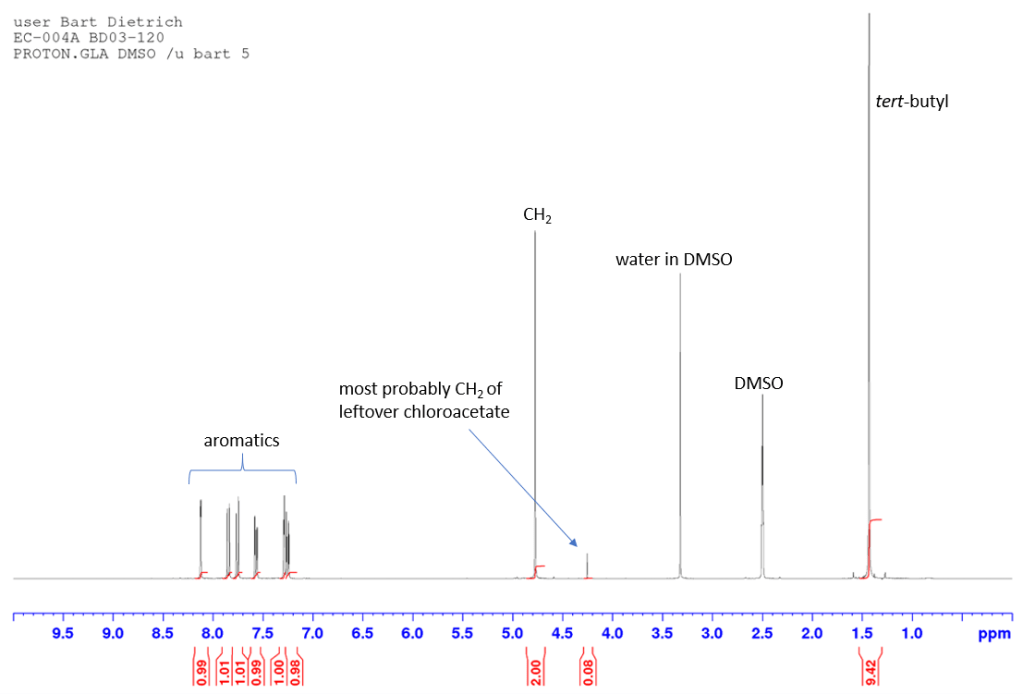

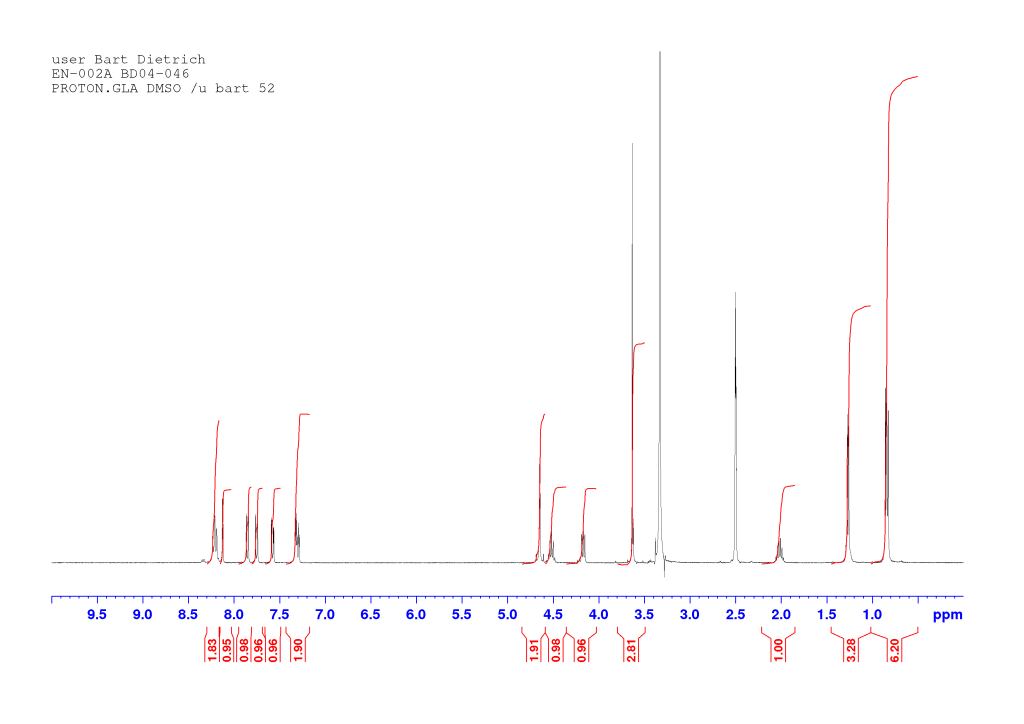

The compound obtained at this stage is rarely very pure and often presents as sticky or waxy solid. But the impurities usually wash out at the next step so no purification is necessary (unless you need a clean sample for data). Just check the NMR contains all signals that should be there (and the integrations are more or less what they should be). Here’s a proton NMR of crude 6-Br-2-NapAOMe. Numerous impurity peaks are present but so are all the expected peaks: this material is good enough for the next step.

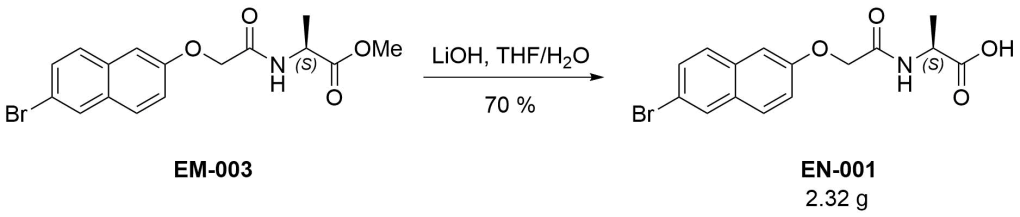

(2S)‐2‐{2‐[(6‐Bromonaphthalen‐2‐yl)oxy]acetamido}propanoic acid (EN-001)

To a solution of EM-003 (3.44 g, 9.39 mmol) in tetrahydrofuran (25 mL) was added a solution of lithium hydroxide (4 eq, 900 mg) in water (25 mL) and the mixture was stirred at room temperature overnight. The turbid mixture was diluted with water, upon which it cleared. It was then poured into 1M hydrochloric acid (ca. 400 mL) and stirred for one hour. The solids were filtered off and dried by azeotropic distillation from acetonitrile. The resulting white solid (3.14 g) contained impurities and was recrystallized from boiling ethanol. The title compound was thus obtained as a white fluffy solid (2.32 g, 70 %).

dH (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) 12.68 (1H, br s, COOH), 8.44 (1H, d, J 7.56, NH), 8.13 (1H, d, J 1.88, HAr), 7.86 (1H, d, J 8.92, HAr), 7.75 (1H, d, J 8.84, HAr), 7.58 (1H, dd, J 8.76, 2.04, HAr), 7.34-7.30 (2H, m, HAr), 4.67 (1H, d, J 14.65, OCHaHb), 4.62 (1H, d, J 14.61, OCHaHb), 4.33 (1H, pseudo quintet, J 7.35, CH*), 1.34 (3H, d, J 7.32, CH3). dC (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) 173.85 and 167.22 (C=O), 156.04, 132.67, 129.92, 129.38, 129.32, 128.97, 128.61, 119.82, 116.59, and 107.53 (CAr), 66.81 (OCH2), 47.29 (CH*), 17.10 (CH3). HRMS (ESI) m/z: [M+Na]+ calcd for C15H1479BrNNaO4 373.9998; found 373.9991.

Comments on 6-Br-2-NapAOH synthesis

This reaction is representative of all lithium hydroxide-mediated ester deprotections commonly carried out in our lab, with some caveats. Most important is how long the reaction is stirred for. In the above example, the reaction is allowed to proceed overnight but the product contains impurities and has to be recrystallised at the end. Some amide bonds are more fragile than others and sometimes amide bond cleavage may become a problem (i.e. you’re going a step back) if the reaction is stirred for too long (e.g. overnight). This is the likely cause of the impurity in the above reaction.

The reaction may be monitored by TLC: the product sticks to the baseline while the starting material will be somewhere above it (given a suitable solvent system of course). The adage that the reaction is complete when it goes clear is not always true. Traces of starting material may remain even then and, conversely, the reaction may not go clear even when complete if insufficient water is present (as in the case above). The latter case may be avoided if more water is used to begin with (e.g. 1.5:1 water/THF rather than the 1:1 ratio used here). A suggested procedure is as follows: stir the reaction for half an hour. If after this time it is still not clear, add some water and see if it clears up. If not, come back in half an hour and check again. If it is clear, run a TLC. If a strong starting material spot is still seen, continue stirring and come back in half an hour. If no starting material is seen on TLC, work up the reaction. If, over the course of several TLCs, the starting material spot is just barely visible (and there is an intense product spot) but doesn’t seem to be going away, work up the reaction anyway. Recrystallisation may be needed.

The lithium hydroxide is used in excess (4 equivalents). Even though the reaction is formally catalytic in nature, you will be waiting forever if you only use a catalytic amount of LiOH. Four equivalents is a trade-off between too much (increased amide bond cleavage) and too little (slow reaction) arrived at entirely by chance: it generally works well enough so that’s what I use.

When it comes to the workup, some people add hydrochloric acid to the reaction mixture. I prefer to add the reaction mixture in portions to quickly stirred hydrochloric acid. The rationale behind this is similar to adding the TFA/chloroform mixture to ether in the tert-butyl ester deprotection higher up on this page. In the case of lithium hydroxide-mediated ester deprotections, it is less clear that this inverse approach is beneficial: the product often coats the stirrer bar and sides of the reaction vessel and has to be scraped off anyway. Do whatever you want, so long as you use a fairly large amount of hydrochloric acid.

After filtering off the product and washing it with water in the filter it may still contain some HCl and lithium salts which may be enclosed inside larger lumps that haven’t been broken up. Simply washing with more water in the filter will not help. Transfer the solid into an Erlenmeyer flask, add water and a large stirrer bar and stir vigorously for 20 minutes. The stirrer bar should be chunky enough and move fast enough so that it can break apart any larger lumps of your compound. Then filter again. Just to be sure, I tend to repeat the stirring-in-water procedure once more.

After the last filtration, leave your compound on the filter with the vacuum on for a while. This will remove the bulk of the water, but your compound will still be quite wet. Now is a good time for an NMR (before you spend time drying your compound which may not be necessary depending on what the next step is to be). If the NMR still shows large amounts of starting material, you should probably put your compound back into the same reaction conditions to let the reaction complete (doesn’t matter if the compound is still wet in that case). If there’s only a small amount of starting material left, you may be able to recrystallise it (if you’re using a water-miscible solvent for that, e.g. ethanol, then it won’t matter if your compound is still a bit wet).

If, on the other hand, your compound is clean (or you want to recrystallise it from a solvent which is not miscible with water, e.g. ethyl acetate), then it needs drying. You can try azeotropic distillation with acetonitrile or stick it in the vacuum oven (make sure there is enough dessicant in the oven!). Simply putting it in an evaporating dish on a hot plate at 50°C in the fume hood overnight should also do the job.

Having the compound clean and free of starting material at this stage (even though it is not the final compound in the synthesis) is important! The next step is another IBCF/NMM coupling with the next amino acid ester and the resulting product is not usually purified so any starting material from the current step will still be present in it (and in any case, these two compounds would in all likelihood be impossible to separate). The step after that is another LiOH deprotection. So you’ll be deprotecting a mixture of two esters (the one obtained in the step after the current one, and some leftover starting material from the current step which may now decide to allow itself to be deprotected): the result is that your final compound two steps from now (in the current example BrNapAV-OH) will be contaminated with some of the compound you’re making in the current step (BrNapA-OH). Separating these two may be difficult!

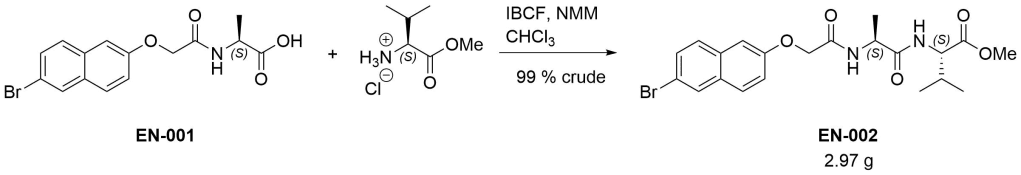

Methyl (2S)‐2‐[(2S)‐2‐{2‐[(6‐bromonaphthalen‐2‐yl)oxy]acetamido}propanamido]‐3‐ethylbutanoate (EN-002)

To a suspension of EN-001 (2.26 g, 6.42 mmol) in chloroform (50 mL) was added isobutyl chloroformate (1 eq, 833 µL) followed by N-methylmorpholine (1.1 eq, 776 µL). After 10 minutes, L-valine methyl ester hydrochloride (1.05 eq, 1.13 g) and another portion of N-methylmorpholine (1.1 eq, 776 µL) were added and the reaction was stirred overnight. It was then diluted with chloroform, washed in turn with 1M hydrochloric acid and brine, dried (MgSO4), and evaporated under reduced pressure. The resulting beige solid (2.97 g, 99 % crude) was used as is in the next step. A small amount was purified via column chromatography (1:9 ethyl acetate/dichloromethane) to yield an analytical sample. The oil thus obtained presented as a waxy solid. It was dissolved in a small amount of dichloromethane, triturated with n-hexane and evaporated, giving a white solid. Residual n-hexane (< 1 %) is seen in the NMR.

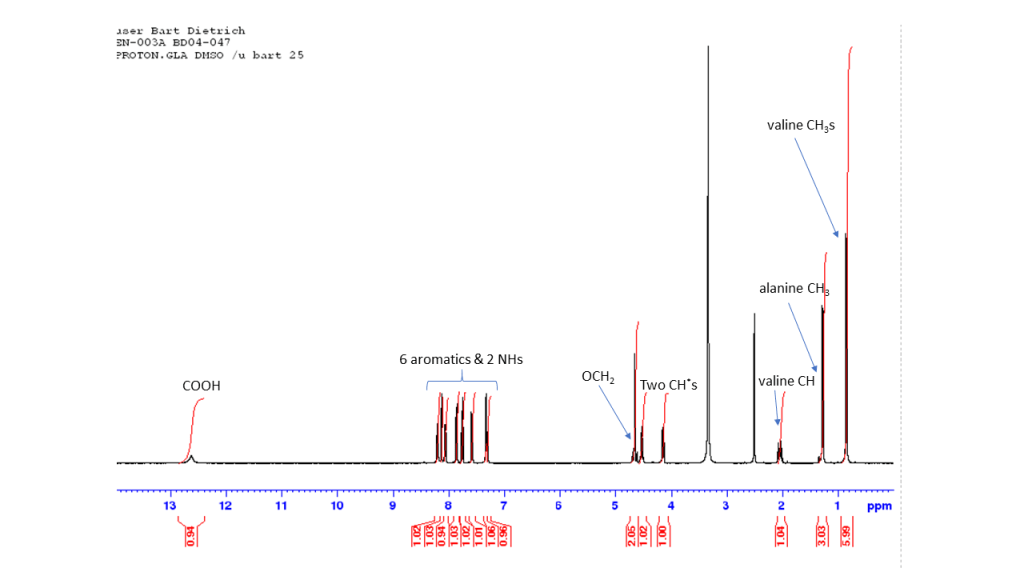

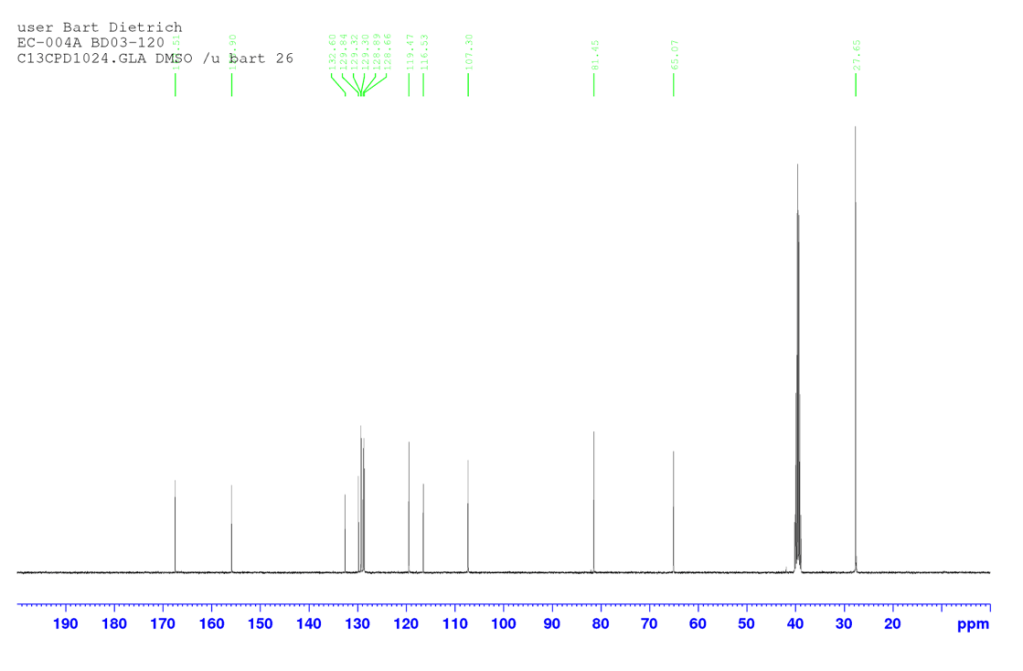

dH (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) 8.22 (1H, d, J 8.92, NH), 8.20 (1H, d, J 8.64, NH), 8.12 (1H, d, J 1.76, HAr), 7.85 (1H, d, J 8.96, HAr), 7.75 (1H, d, J 8.80, HAr), 7.58 (1H, dd, J 8.74, 2.02, HAr), 7.33-7.28 (2H, m, HAr), 4.67 (1H, d, J 14.61, OCHaHb), 4.63 (1H, d, J 14.61, OCHaHb), 4.55-4.48 (1H, m, CH*), 4.17 (1H, dd, J 8.04, 6.24, CH*), 3.63 (3H, s, OCH3), 2.06-1.97 (1H, m, CH(CH3)2), 1.27 (3H, d, J 7.00, CH*CH3), 0.85 (3H, d, J 6.40, CH(CH3)2), 0.83 (3H, d, J 6.40, CH(CH3)2). dC (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) 172.37, 171.84, and 166.92 (C=O), 155.98, 132.66, 129.91, 129.36, 129.30, 128.96, 128.65, 119.70, 116.57, and 107.47 (CAr), 66.79 (OCH2), 57.40 (CH*), 51.68 (OCH3), 47.57 (CH*), 29.83 (CH(CH3)2), 18.88 (CH(CH3)2), 18.38 (CH*CH3), 18.14 (CH(CH3)2). HRMS (ESI) m/z: [M+Na]+ calcd for C21H2579BrN2NaO5 487.0839; found 487.0837.

Comments on 6-Br-2-NapAVOMe synthesis

This is analogous to the synthesis of 6-Br-2-NapAOMe and all comments there apply equally here.

(2S)‐2‐[(2S)‐2‐{2‐[(6‐Bromonaphthalen‐2‐yl)oxy]acetamido}propanamido]‐3‐methylbutanoic acid (EN-003)

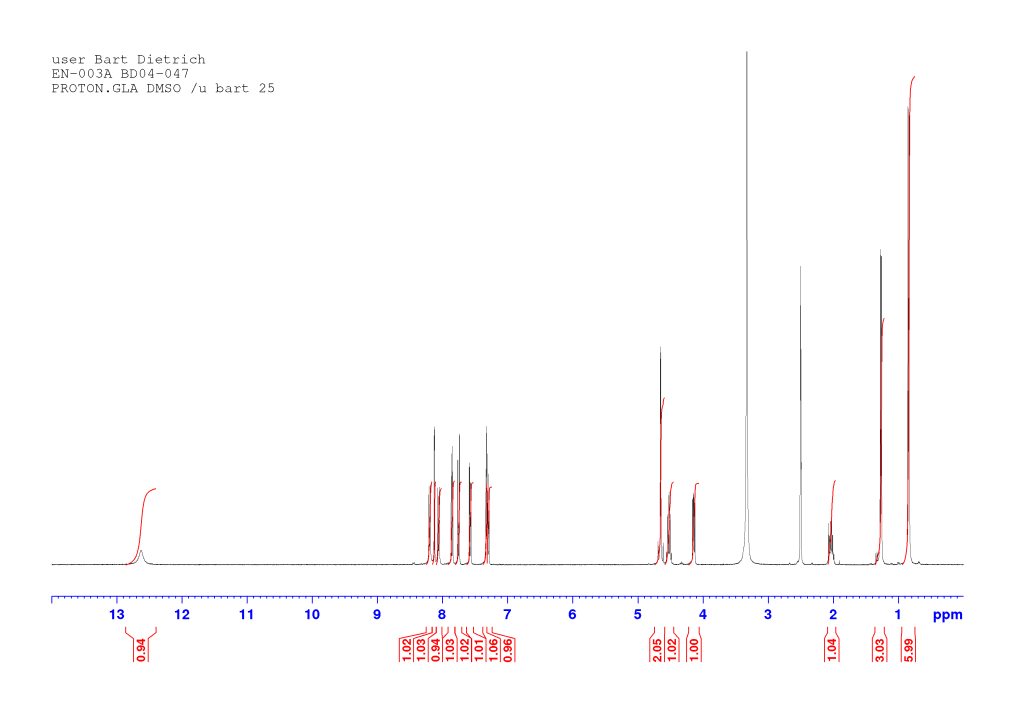

To a solution of EN-002 (2.71 g, 5.82 mmol) in tetrahydrofuran (30 mL) was added a solution of lithium hydroxide (4 eq, 558 mg) in water (30 mL) and the reaction was monitored by TLC. After about one hour, the starting material had been consumed. The mixture was poured into 1M hydrochloric acid (ca. 200 mL) and stirred for one hour. The precipitated sticky solids were filtered off and washed with water in the filter. Recrystallization from boiling acetonitrile afforded the title compound as a white solid (1.84 g, 70 %).

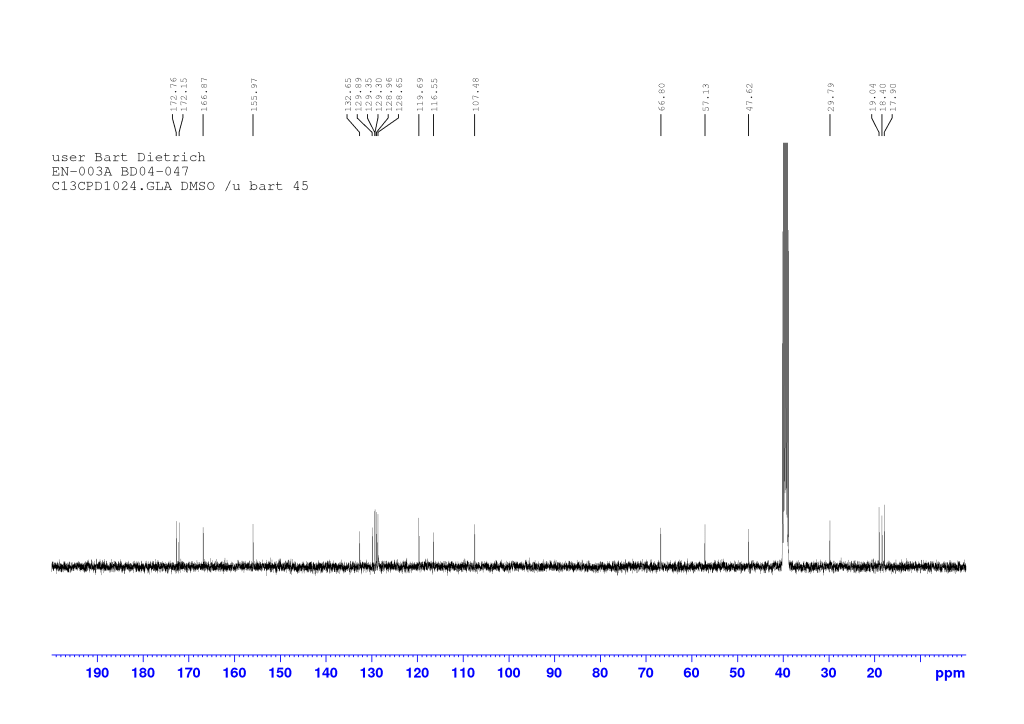

dH (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) 12.63 (1H, br s, COOH), 8.20 (1H, d, J 7.64, NH), 8.12 (1H, d, J 1.88, HAr), 8.06 (1H, d, J 8.52, NH), 7.85 (1H, d, J 9.00, HAr), 7.75 (1H, d, J 8.84, HAr), 7.58 (1H, dd, J 8.76, 2.04, HAr), 7.33 (1H, d, J 2.36, HAr), 7.30 (1H, dd, J 8.88, 2.52, HAr), 4.67 (1H, d, J 14.41, OCHaHb), 4.63 (1H, d, J 14.61, OCHaHb), 4.56-4.49 (1H, m, CH*CH3), 4.14 (1H, dd, J 8.50, 5.70, CH*CH), 2.07-1.99 (1H, m, CH*CH), 1.27 (3H, d, J 7.00, CH*CH3), 0.84 (6H, dd, J 6.78, 0.82, CH(CH3)2). dC (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) 172.76, 172.15, and 166.87 (C=O), 155.97, 132.65, 129.89, 129.34, 129.30, 128.96, 128.65, 119.69, 116.54, and 107.48 (CAr), 66.80 (OCH2), 57.13 (CH*CH), 47.62 (CH*CH3), 29.79 (CH*CH), 19.04 (CH(CH3)2), 18.40 (CH*CH3), 17.90 (CH(CH3)2). HRMS (ESI) m/z: [M+Na]+ calcd for C20H2379BrN2NaO5 473.0683; found 473.0674.

Comments on 6-Br-2-NapAV synthesis

This reaction is analogous to the synthesis of 6-Br-2-NapAOH and all comments there apply equally here. An annotated proton NMR of the compound follows.